Reflecting on Warhol

Andy Warhol's prediction that everyone will be world-famous for fifteen minutes was intended to undermine the idea that anyone 'deserved' to be famous and highlight that with modern media a broader collection of people could be known by everyone (for only a little time, admittedly). This is related to the broader idea that globalisation and the end of the old media etc. would lead to more voices being heard and a decrease in the dominance of cultural conversations by a few individuals. I have highlighted before (in my post http://reciprocans-reciprocans.blogspot.com.au/2012/04/is-trade-in-ideas-free-interrogating.html) that the marketplace for ideas is fundamentally unfree and in this post I wish to examine whether the broader idea that we have a more pluralistic (or less 'concentrated' perhaps) culture is at all valid. I can't help myself, I'm addicted to a life of material

So this begs two questions: How do people get famous? And is this more or less concentrated than before?

I don't mean I want to examine the marketing of celebrity (which is detailed for those interested in a reasonably old Economist post: http://www.economist.com/node/4344144) nor do I want to get into a debate about the merits of Madonna or Lady Gaga etc (which I have previously defended at http://reciprocans-reciprocans.blogspot.com.au/2012/05/baby-im-your-biggest-fan-ill-follow-you.html), I mean the process by which the works, knowledge of their lives or writings of famous individuals spread in society.

I want to make two claims: really famous works (or the fame of celebrities) tend to spread at a slow rate until they reach a 'critical mass' at which point they spread exponentially (seemingly without effort) and that this and the processes of globalised capitalism make a 'winner take all' culture more pervasive (with qualifications) than before.

Warhol may have been right that many people are famous for short periods, but it is still true that there are particular subjects whose fame does not fade as easily who still dominate our culture.

How Things Get Popular

Gabriel Rossman in his excellent book Climbing the Charts discusses how most ideas (or works etc.) either spread 'within' a social network (think of your friends recommending a song or a new cardigan) or 'from without' (e.g. promoting the Batman film with a huge advertising release). The latter type produces the more predictable pattern that the work will do huge business initially but then fade away quickly, for example with Twilight box office sales.

Charts courtesy of Sociological Images

Now, most works function like this- they have some initial scales (which are obviously scale variant) and then peter off. But some films or songs etc work in the first way- they become 'viral' which means that their sales are 'S-shaped', they are unpopular initially and then suddenly when they reach a critical mass of popularity, spike! As an example: the box office results for My Big Fat Greek Wedding:

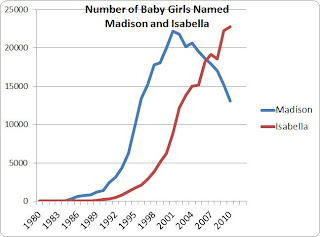

This even applies to baby names, as you can see in the chart below, Isabella spiked as a social phenomenon from without whereas Madison spiked initially due to the movie Splash (released in 1984) and then became a runaway success until fading in the late 1990s.

Now, what does this all mean? Well, if you do get famous, with the exception for those whose 'fame' is the very brief glimpse on the nightly news- you tend to become famous for a longer period than Warhol's quip might suspect- see the Kardashians, for instance. Once you get people initially interested in a product, work etc. it can spread 'virally' throughout social networks till the popularity of that product, work etc. is self sustaining, at least for a time.

But, since I'm an economist at heart, what are the consequences then for the monetary side?

The Rise of Winner Takes All Markets

As Adorno puts it in The Culture Industry, previously you might've had a tenor for each major town and a group of tenors in a major city- but now, thanks to technology, everyone can listen to Pavarotti- who is almost certainly not so much better than other tenors that he deserves most of the attention/profit but might be a bit better and able to be marketed more easily. With the invention of the internet in particular, it is very easy now for the works of certain people to spread through the whole population without limitations on say actually being able to go to a concert hall or wait for a new print run of Harry Potter etc.

Now, this is obviously not entirely the case- 'within' trends do exist as I noted, as evidenced by the explosion of new acts and writers who have risen from the internet (for example Justin Bieber). But the idea that new technology was solely going to lead to pluralism or the demise of persistent celebrity is false- indeed popular Western acts like Madonna etc. have displaced some locally famous acts across the developed and developing world. As there is an ability to reach more people, the 'market' for fame and status can devolve into a 'winner takes all' market. In economics, you can have a market where scaling up actually increases the returns you make on an investment (as opposed to what you might think is more intuitive- where scaling up decreases efficiency). If this is the case, then superstars can basically extract a lot of profit when they get to a certain critical mass of popularity.

What are the limitations on this? Well, most new adaptions only get to a certain level of popularity before they peter out- with the exception of televisions, there is almost no technology owned by close to the whole population of the United States, for instance. Also, as we have seen time and time again (particularly with the youth), people will either intentionally or otherwise break the mould of the system- perhaps creating alternative or subculture communities as a consequence.

Conclusion

The tide of any cultural change is hard to predict- who would have thought that 'Call me Maybe' would become so popular or that a book about a boy wizard who goes off to wizarding school would enthral a huge reading public? But the general outline of the complex and varied system that is 'culture' can be at least traced. Fame might be quicker to obtain now than before, but it still often lasts and can provide particularly high profits. In the end, some people are still famous for a lot longer than 15 minutes and most people are only noticed for fifteen seconds, at best.

--

Dan Gibbons is a third year Bachelor of Commerce (Economics) student at the University of Melbourne. He has a forthcoming publication in Intergraph: A Journal of Dialogic Anthropology (about memory and nationalism) and is currently submitting papers on the rise of modern consumerism, the role of criminology theory in literary criticism and the institutional theory of nationalism. Dan is a keen debater and public speaker.

No comments:

Post a Comment