With the

publication of On the Origins of Species, Darwin’s theory of evolution by

natural selection has been one of the most profound theories in the biological

sciences in expounding and analysing the physical, genetic and behavioural

diversity of animals. Indeed Darwinian evolution has been a profound theory

outside of the biological sciences – namely it has had remarkable impact in the

social sciences throughout its history. During the nineteenth century, “versions

of Darwinian evolution took centre stage in political and social philosophy and

in the human sciences.” A number of anthropologists came to understand cultural

variation in terms of a linear progression to a cultural apex, then considered

Western civilisation. This interpretation was rebuked by the anthropological

school of cultural relativism and it became essentially taboo by the academy to

utilise evolutionary theory in the social sciences. That said, during the early

to mid-twentieth century a number of sociopolitical movements, such as the Nazi

party and the eugenics movement, appropriated Darwinism to justify the genocide

of certain deemed “unfavourable” and “subhuman” demographics. Such

justifications were strongly condemned by evolutionary scientists as

pseudoscientific and immoral but such utilisation of evolutionary theory in the

social sciences still remained seriously contentious. Then in 1975 the American

entomologist Wilson developed the field of sociobiology as the “systematic

study of the biological basis of all social behaviour in the context of

evolution” and in 1976 the British zoologist Dawkins developed the gene-centred

view of evolution based on “selfish genes” determining natural selection and

consequent behaviour of an organism. Whilst both Wilson and Dawkins primary aims

were with the study of non-human animals, their theories flowed over into the

realms of the social sciences. Indeed there was a profound backlash in the

social sciences academy claiming that sociobiology and the gene-centred view

were ethnocentric, reductionist, determinist and flawed in explaining human

nature. By the 1990s, the debate over human sociobiology culminated in the

development of evolutionary psychology as attempting to respond to the

criticisms against evolutionary theory in the social sciences. Led by Barkow,

Cosmides, and Tooby, evolutionary psychology aimed to understand the “neurobiology

of the human brain as a series of evolutionary adaptations and that human

behaviour and culture thus stem from the genetics and evolution of the brain.” Yet

there still exists and persists contentions from the social sciences,

particularly cultural anthropology, against sociobiology and evolutionary

psychology. This essay will examine the history of the contributions and

criticisms of evolutionary theory in the social sciences, from its racist and

pseudoscientific past to its current contributions. Then it will examine the

contributions and theory of sociobiology and evolutionary psychology as applied

to anthropology in explaining human nature and also examine the contentions and

controversy in the anthropological academy in response to such. Overall this

essay will not delve into the technical details and scientific theory of

evolutionary theory, but rather examine its claims and responses to and from in

the anthropological academy.

Darwin’s

theory of evolution by natural selection has presented an interpretation of

human nature that has been at odds with prevailing theoretical paradigms

throughout its history. The theorisation of human nature through conceptions of

evolution and instinct has been undertaken by such figures as Darwin himself, Hume,

Smith and Huxley who have proposed that the mosaic of human nature stems from innate

human instincts. Whilst this paradigm of evolutionary social science culminated

as essentially “passive and benign contemplations”, the theory of evolution of

natural selection also manifested as bigotry, racism and the apparent

justification of white Anglo male supremacy based on a linear interpretation of

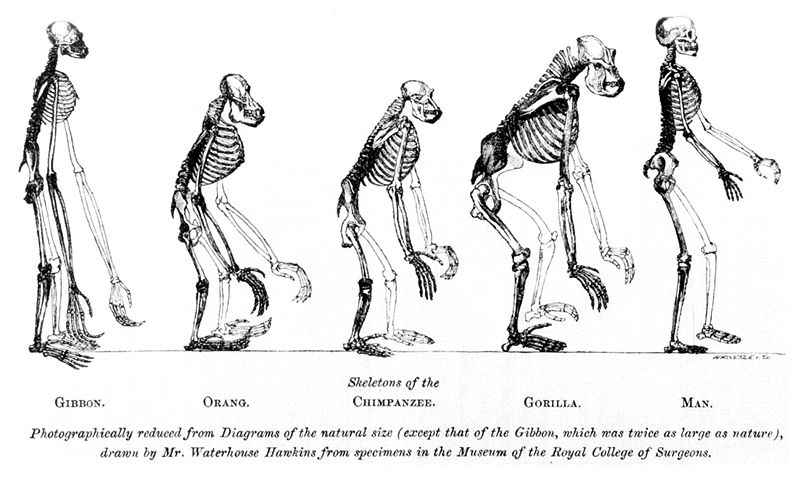

history. The school of social evolutionism in the anthropological academy led

by Tylor, Morgan and Spencer became the dominant paradigm in the late ninetieth

century and became appropriated as Social Darwinism in popular discourses. This

paradigm utilised the framework of evolution to describe the differences

between developed Western civilisations and non-developed “savage” cultures as stemming

from the biological inferiority of the “savages” who were considered more

related to chimpanzees than the superior Anglo-Saxons. Social movements also

took up this school of thought and supported social policies of eugenics and

forced sterilisation of certain demographics such as those in low socioeconomic

statuses, those with disabilities or mental illness, or those from non-white

ethnicities. Key responses to this school came from Boas and Kroeber in the anthropological

schools of historical particularism and cultural relativism. These schools posited

that the history of humanity is not a linear progression to the technological

civilisation of the West but rather that each culture must be understood by “its

own conditions and own particular cultural history.” Yet, there have still been

individuals and groups that support Social Darwinism, culminating in cases such

as the forced assimilation of Australian Aboriginals in the early twentieth

century and the genocide committed by the Nazi regime during 1933 to 1945.

After the Second World War, as Degler posits “the utilisation of the theory of

the biological sciences in the social sciences and the ‘biologicisation’ of

human nature became a taboo” due to the profound consequences of its

appropriations.

During the

1970s there was a revival in the theory of evolutionary theory with advances in

molecular biology, genetics, computer science and mathematical game theory. This revival was primarily aimed at explaining non-human

animal behaviour and was largely led by Wilson and Dawkins along with other

evolutionary theorists. Although this was the primary aim of the science, both

Wilson and Dawkins still theorised on the evolution of human behaviour using

the same paradigm of evolutionary theory of the study non-human behaviour. There

was profound backlash in the social sciences, primarily by Lewontin, Rose, and

Kamin and Sahlins with the scientific reductionism and biological determinism

of sociobiology in explaining culture, but also controversy surrounding the

ideological and ethical implications of such. Thus the theorists of

sociobiology then responded to such criticism and controversy with the

development of the field of evolutionary psychology. Led by Barkow, Cosmides

and Tooby, evolutionary psychology attempted to redress the claims of

reductionism and determinism by focusing on the dichotomy of nature and nurture

through holistically studying the neurobiological, cognitive and psychological

factors of human nature. Yet, the paradigm of evolutionary psychology has also too

been met with profound criticism from the anthropological academy. Despite such

criticism over legitimacy and usefulness, the fields of sociobiology,

evolutionary psychology and the general application of evolutionary theory in

the social sciences, have been increasingly taken up in the biological and social

sciences academies.

The

majority of ethical, practical and theoretical contentions in the

anthropological academy surrounding the application of evolutionary theory to

explain human nature stem from the reductionism and genetic determinism of

evolutionary theory. Indeed the question of how in the confines of the so

perceived savage, impersonal and selfish world of Darwinian natural section can

complex social structures and cultural norms come about is indeed important.

Sociobiology and evolutionary psychology as they manifest in the academic and

popular literature have been rebuked by anthropologists and other cultural

theorists as being “ethnocentric, reductionist, determinist, and

philosophically reprehensible.” Critics level evolutionary theory “is merely

academic fancy foot work away from the archaic and pseudoscientific” school of

social evolutionism of the nineteenth century, that it explicitly and implicitly

makes “false, flawed and unsubstantiated assumptions about social, political,

economic, and cultural processes”, and that even the presumption of a “human

nature itself is flawed.” Indeed as Sahlins has stated, evolutionary theory in

the social sciences is “at its worst pseudoscientific and racist and at its

best it is quasi-scientific based on flawed principles and methodology with a

profound misunderstanding of the dynamics of culture.” The responses to these

claims by evolutionary theorists have centred on pointing out the “fundamental

biological basis of humans, being an animal species just like any other” but

also pointing out the “naturalistic fallacy between making descriptive and

normative judgements."

The theory

of sociobiology and evolutionary psychology is predicated, by definition, on reducing

human behaviour to an evolutionary and biological basis. According to Lewontin and

Sahlins this does away with the cultural forces of acculturation and diffusion

and other social, economic and political dynamics. Indeed explaining human

behaviour by “reducing it down to the genes of the body and modules in the

brain” fundamentally “neglects to recognise the power of culture in shaping and

reshaping the human mind.” Thus the theorisation of the gene and or the brain

being the paramount determiner in human behaviour is flawed as it “restricts

the interpretation of behaviour and its cultural context.” Rather, Lewontin

propounds a dialectical and interactionist interpretation of human behaviour in

response to the reductionism as “it is not just that wholes are more than the

sum of their parts, it is that parts become qualitatively new by being parts of

the whole.” Lewontin propose that dialectical explanations are more effective

and holistic in explaining human behaviour in contrast to the “reductionist

calculus of the evolutionary neurobiological and gene-centred view of culture.”

In response, evolutionary theorists propose that reductionism is an “important

scientific principle.” Moreover such theorists as Barkow and Wilson propose

that the theory of evolutionary psychology also seeks a holistic interpretation

of human nature via genetic, cognitive, neurobiological and psychological

processes “based on the fact that humans have evolved to environments with

culture – that culture is not independent of evolution, but rather biology is

the precursor.” Indeed “culture is sometimes advanced as competing with

explanations that invoke evolutionary psychology, most frequently when cross-cultural

variability is observed” and these “cultural explanations invoke the notion that

differences between groups are prima facie evidence that culture is an

autonomous causal agent.” Evolutionary theorists respond to these criticisms by

stating that “cultural explanations are more or less cultural reductionism” and

“ignorant of the role of biology and innate characteristics” that have evolved

in the human species.

Along with

the claims and criticisms of reductionism against sociobiology and evolutionary

psychology is biological determinism. The critics label sociobiology and

evolutionary psychology as biological determinist and that evolutionary theory

is ignorant of the forces of nurture and the capacity of culture and social

environments to shape and reshape human nature, but also that evolutionary

theory facilitates and entrenches racism, sexism and prejudice. Indeed major

criticism against sociobiology and evolutionary psychology that stems from the

ethical, political and social implications of their theoretical underpinnings

and findings. The critics of evolutionary psychology propose that evolutionary

theory promotes or at least enables racism and sexism and does to re-entrench

out-dated perceptions of sex and race. This criticism came from key findings in

evolutionary psychology that the male and female brains evolved differently and

thus possess different cognitive and behavioural hardwiring and that certain

ethnicities are more likely to behave in certain ways or are more susceptible

to certain diseases. Indeed, some evolutionary theorists, such as Jensen have

even claimed that that intelligence is inheritable, that certain races are more

intelligent than others, and that racial economic equality is unattainable.

Thus it is proposed that just as the historically dominant class ideologies

that supported the oppression of women and ethnic minorities had strong pseudoscientific

justifications, in the form of assertions that women and ethnic minorities were

genetically inferior, sociobiology and evolutionary psychology makes it

possible again to hold such beliefs.

All this

criticism has been strongly responded to by evolutionary theorists primarily

based on pointing forth the naturalistic fallacy and that “sociobiology and evolutionary

psychology are scientific disciplines with no social agenda.” It is also put

forward that the frameworks of sociobiology and evolutionary psychology

dissolve dichotomies of nature versus nurture, innate versus learned, and

biological versus culture. It is not biological determinism but rather an

understanding that genes and other biological factors predispose certain

behavioural traits and therefore culture. Moreover, it is proposed that the

biological determinism perceived of evolutionary theory in the social sciences “as

being seen to be antithetical to social or political change is evidently

historically falsified.” Evolutionary theorists respond with that evolutionary

psychology does not privilege or prejudice individuals or groups but rather

just seeks to describe and that the claims on racial inequality being

inevitable by Jensen and Herrnstein have been discredited in the evolutionary

theory by fellow theorists such as De Waal and Pinker. Indeed, it has been

asserted that critics have been putting forth critiques based on personal

political and ethical values rather than any empirical or explanatory factors

and thus the attacks against evolutionary theory have been made on “non-scientific

grounds”. Sociobiologists and evolutionary psychologists “should and do

acknowledge the role of ideology and politics in the formation and support of

scientific paradigms” but do not let it influence their own paradigm. Moreover

it is noted that “genetically determined mechanisms do not imply genetically

determined behaviour” and thus the theory of sociobiology and evolutionary

psychology is not predicated on genetic determinism. Fundamentally critics do

not recognise the naturalistic fallacy in their critiques of the ethical

implications of evolutionary theory. Indeed “an explanation is not a

justification” and neither sociobiology nor evolutionary psychology attempt to

justify the existence of social hierarchies, racism or sexism – “when they are

and have been used to justify such than evidently that is not scientific.” It

is posited that any “politically incorrect assertions of evolutionary psychology

are based on considerable empirical evidence” and indeed critics are welcome to

challenge the evidence or provide testable alternative explanations. Overall it

is a profound misunderstanding of sociobiology and evolutionary psychology to

claim it is biological determinist when it takes in genetic, neurobiological,

and cultural evolution of human behaviour. Thus when the theoretical paradigm

fails to achieve such a spread of looking at genetic, neurobiological and

cultural factors, theorists agree with critics that such a paradigm is indeed

flawed.

The

resurgence of evolutionary theory in the social sciences has indeed been a

contentious and controversial one with much criticism being levelled against it

but it also has managed to make constructive contributions to the

anthropological academy. With its archaic and pseudoscientific beginnings in

the schools of social evolutionism and Social Darwinism of Tylor, Morgan and

Spencer arguably behind it, Wilson and Dawkins and then Barkow, Cosmides and

Tooby and others transformed the application of evolutionary theory in the

social sciences. Yet indeed the theory of sociobiology and evolutionary theory

was met with critical claims of ethnocentrism, determinism and reductionism by Sahlins,

and Lewontin, Rose, and Kamin and others, it responded with arguments stemming

from the naturalistic fallacy and that it is a misunderstanding of the theory

to label it determinist. Indeed the majority of theorists, both evolutionary

and non-evolutionary, acknowledge that it is flawed and invalid to make purely

reductionistic and biologically determinist explanations for human nature,

specifically culture. Thus evolutionary theory attempts to employ a holistic

interpretation based on neurobiological, genetic and cultural factors whilst

firmly grounded in the understanding that humans have evolved with culture. Overall,

whilst evolutionary theory in the social sciences, particularly cultural

anthropology, has been and still largely is contentious, it is becoming the

popular and prevailing paradigm once again. Thus sociobiology and evolutionary

psychology must not revert to their natal beginnings in the application of the

human sciences through justifying racism and sexism and other forms of violence

and prejudice of the times of Social Darwinism. Fundamentally evolutionary

theory must progress cautiously in explaining the politically, socially and

morally sensitive issues that exist. Indeed making politically incorrect

findings through evolutionary theory is essentially inevitable and should not

be refrained from, but its theorist must recognise the consequences as they

manifest in the social environment that it exists in.

Tasman Bain is a second year Bachelor of Arts (Anthropology) and Bachelor of Social Science (International Development) Student at the University of Queensland. He is interested evolutionary anthropology, social epidemiology and philosophy of science and enjoys endurance running, reading Douglas Adams, and playing the glockenspiel.