I am as free as nature first made man,

Ere the base laws of servitude began,

When wild in woods the noble savage ran.

The Conquest of Granada (1670)

John Dryden (1631 – 1700)

English poet and playwright

Introduction

This is the second part in the

series of comparative analysis of hunter gatherers and agricultural societies

which will be focusing on socioeconomics.

My other post laid out the empirical nature of the health nutrition of both societies

demonstrating that the diet of hunter gatherers was far more healthy and

diverse than that of agricultural societies. I qualified this by conceding

that, in theory, through modern medicine and preventative health we can offset

the harms of the Western diet to our Palaeolithic genome and this has

translated into higher life expectancy since the Renaissance for Europeans.

This post I will be looking at three areas – cooperation and egalitarianism;

labour and leisure; and peace and conflict – and providing analysis and comparison

between hunter gatherers and agricultural societies. In this post I aim to

address some misconceptions commonly found about hunter gatherer socioeconomics

in an empirical manner without making any serious normative value judgements. Let

us begin with some context to this interesting topic.

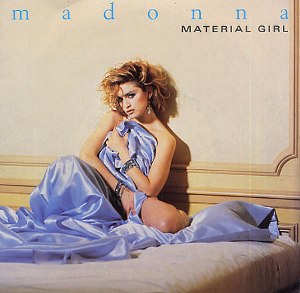

Hadza Bushmen of Tanzania having lunch

The State of Nature from Leviathan to Stone Age Economics

Throughout the history of

western philosophy the state of nature has been a central concept for

expounding and justifying various political, social, economic and moral ideals.

The English philosopher Thomas Hobbes (1588 – 1679) was one of the first to

employ this though experiment in his book Leviathan

(1651) written during the English Civil War (1642–1651). In it he proposed

the necessity for an absolute monarchy and strong central government to

constrain and curb the brutish instincts of humans that are found in the

original position where there is no civil society. According to Hobbes, the

state of nature was marked by bellum

omnium contra omnes (the war of all against all) and that there was:

No Knowledge of the face of the Earth; no

account of Time; no Arts; no Letters; no Society; and which is worst of all,

continual fear, and danger of violent death; And the life of man, solitary,

poor, nasty, brutish, and short.

Indeed this perspective of the

state of nature by Hobbes has been one of the prominent interpretations for humanity’s

instincts and has been employed by various political philosophers and national

leaders to justify certain policies throughout history. Yet, in 1689, the

English philosopher John Locke (1632 – 1704) offered and expounded a

fundamentally different perspective on the state of nature. In Two Treatises of Government Locke argued

for democratic governance in opposition to Hobbesian absolute monarchy and came

to a conclusion about the state of nature:

The state of nature has a law of nature to

govern it, which obliges every one: and reason, which is that law, teaches all humankind,

who will but consult it, that being all equal and interdependent; no one ought

to harm another in his life, health, and liberty. The natural state is also one

of equality in which all power and jurisdiction is reciprocal and no one has

more than another. It is evident that all human beings – as creatures belonging

to the same species and rank and born indiscriminately with all the same

natural advantages and faculties – are equal amongst themselves.

Indeed, this interpretation of

the state of nature as being far from the Hobbesian struggle lead to various

characterisations of those living in the state of nature as being “noble

savages”. This concept is commonly associated with the Genevan philosopher Jean-Jacques

Rousseau (1712 – 1778), but interestingly the first use of the term appears in

1670 in The Conquest of Granada, a

play by English poet and playwright John Dryden. Certainly, Rousseau took on

board this concept and in his Discourse

on the Origin and Basis of Inequality among Men (1754) he states:

I know that civilized men do nothing but boast

incessantly of the peace and repose they enjoy in their chains. But when I see

barbarous man sacrifice pleasures, repose, wealth, power, and life itself for

the preservation of this sole good which is so disdained by those who have lost

it; when I see animals born free and despising captivity break their heads

against the bars of their prison; when I see multitudes of entirely naked

savages scorn European voluptuousness.

When the British explorer

Captain James Cook came across Australia he was of a similar opinion to Rousseau.

In the entry of 23 August 1770 into the Journal of H.M.S. Endeavour, Cook opinionated:

The natives of New Holland may appear to

some to be the most wretched people of earth, but in reality they are far happier

than we Europeans, as they are wholly unacquainted with the superfluous conveniences

so much sought after in Europe. They live in a tranquillity which is not disturbed

by the Inequality of Condition: The Earth and sea of their own accord furnishes

them with all things necessary for life, they covet not magnificent houses, household-stuff.

In short they seemed to set no value upon any thing we gave them. This in my

opinion argues that they think themselves provided with all the necessities of life

and that they have no superfluities.

It must be noted that Hobbes,

Locke and Rousseau all lacked any empirical evidence to substantiate their

claims of the original position and state of nature of humankind and even Cook

lacked the thorough methodology to make such empirical claims. Indeed, it is

contested to weather Hobbes even proposed his

Leviathan as the reality of the state of nature or rather proposed

it as a philosophical though experiment. Either way, with the wax and wane of

colonialism and the decline of racist anthropology, by the 1960s a number of

anthropologists were conducting ethnographic fieldwork in some of the last hunter

gatherer societies in existence. A prominent radical anthropologist was

Marshall

Sahlins, now Distinguished Professor of Anthropology at the University of

Chicago. In 1974 he wrote

The

Original Affluent Society in

Stone

Age Economics arguing that hunter gatherer societies were actually affluent

insofar as their material expectations closely matched their means to obtain

those expectations and they had limited wants and unlimited means. As stated:

Hunter-gatherers consume less energy per

capita per year than any other group of human beings. Yet when you come to

examine it the original affluent society was none other than the hunter and

gatherers in which all the people's material wants were easily satisfied. To

accept that hunters are affluent is therefore to recognise that the present

human condition of man slaving to bridge the gap between his unlimited wants

and his insufficient means is a tragedy of modern times.

This concept of the Original Affluent Society seriously

challenged the orthodoxy of the time of Hobbes in political and social

philosophy and of Homo economicus in

classical economic theory. It is with this context that I shall begin my

analysis of the empirical evidence from the archaeological and ethnographic

records of hunter gatherer societies – the state of nature.

Cooperation and Egalitarianism: Equity, Gift Economy and Challenges to Homo economicus

Inequality is not an intrinsic

or natural feature of human societies – the social, political and economic

organisation of hunter gatherers, from the Hadza to the Inuit, inevitably tends

to be that of egalitarianism. This fact comes down to a number of factors

spurring it on: ecological constraints necessitating equity for the group, the

natural selection of cooperative and prosocial behaviours, but also through

cultural constructs and social networks to maintain, facilitate and enforce

equality. Cooperation is fundamental in these hunter gatherer societies, and as

a David Attenborough

documentary

shows, it is possible through cooperation that 3 Dorobo hunters of Kenya can

scare off 15 hungry lions from a recently deceased game and go home with free

meat to feed the tribe. Indeed James Woodburn, Emeritus Professor of

Anthropology at the London School of Economics, states that hunter gatherers

are “aggressively egalitarian” because this egalitarianism is a necessity for

their survival. Some of the most profound examples of

altruistic

punishment of freeriders occur in these hunter gatherer societies, and some

of the most profound examples of how

cooperative

and prosocial behaviours are incentivised are found in hunter gatherers

societies.

Recent

ethnographic research and statistical modelling – published in Nature by a

team of anthropologists and statisticians from Harvard University, University

of California at San Diego and University of Cambridge – has uncovered the

networks

of cooperation of the Hadza in Tanzania and how cooperators cluster

together in order to outcompete freeriders and egotists and how these networks

are found in modern social interactions (

Coren

L. Apicella of Harvard University explains it

here). Hunter gatherers

are profoundly the antithesis to

Homo economicus

– their

society is

based on the gift economy where there is complete communal sharing of

resources and selfishness is fundamentally taboo and dominators are abhorred.

The market economy is a myth

when it comes to the subsistence gift economies of hunter gatherers, as

John M. Gowdy, Professor

of Economics and Social Sciences at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, shows

in the

Cambridge

Encyclopaedia of Hunters and Gatherers. Among the Hadza people of Tanzania there

are elaborate rules to ensure that all meat from a hunting expedition is

equally shared. Hoarding, or even having a greater share than others, is

socially unacceptable and egotists are punished. Apart from personal items,

such as tools, weapons, or jewellery, there are sanctions against accumulating

possessions, not least because the nomadism of hunter gatherers makes possessions

a nuisance. Gowdy proposes that the study of the state of nature, that of our

first way of life as hunter gatherers, offers fundamental challenges to the economic

orthodoxy of the neoclassical and neoliberal philosophy of

Homo economicus:

- The economic notion of scarcity is a social

construct, not an inherent property of human existence.

- The separation of work from social life is not a

necessary characteristic of economic production.

- The linking of individual wellbeing to

individual production is not a necessary characteristic of economic

organization.

- Selfishness and acquisitiveness are aspects of

human nature, but not necessarily the dominant ones.

- Inequality based on class and gender is not a

necessary characteristic of human society.

There has been extensive

ethnographic research on the socioeconomic structures of hunter gatherers around

the world and the majority of evidence suggests that there are indeed profound

egalitarian. In

Egalitarian

Societies, published by the Royal Anthropological Institute, Woodburn lays

out the social and economic organisation and structures of hunter gatherer

societies that are egalitarian. These societies (such as the Mbuti of the

Congo, the !Kung of the Kalahari, the Hadza of Tanzania, the Batek of Malaysia,

the Paliyan of South India, the Awá-Guajá of Brazil, the Aeta of the Philippines,

and Mardu of western Australia) display profound social, economic and gender

parities which are maintained by cultural constructs to enforce and coerce

egalitarianism and social networks of clustering cooperative and prosocial

behaviours. Woodburn establishes four key characteristics of such immediate

return societies that are conducive for egalitarianism:

- Social groupings are flexible and constantly

changing in composition.

- Individuals have a choice of whom they associate

with in residence, in the hunting and gathering food quest, in trade and

exchange, and in ritual contexts.

- People are not dependent on specific other

people for access to basic requirements.

- Relationships between people, whether

relationships of kinship or other social exchanges, stress sharing and

mutuality not involving long-term binding commitments.

The equality found in these hunter

gatherer societies is achieved through direct individual access to resources;

through direct individual access to means coercion and means of mobility which

limit the imposition of control; through procedures which prevent accumulation

and impose sharing; through mechanisms which allow goods to circulate without

making people dependent upon one another. With these value systems of

non-competition, egalitarian hunter-gatherers limits the development of social

stratification and in principle extend equality to all.

Ethnographic research on the Mardu

people in Western Australia by

Robert Tonkinson, Emeritus

Professor of Anthropology at the University of Western Australia and author of

The Mardu

Aborigines: Living the Dream in Australia’s Desert,

shows similar structures and characteristics. The potential for

inequality in Mardu society is submerged due to the considerable weight of an

ethos and praxis of mutual aid and a notable stress on individual autonomy. Relationships

that are structurally asymmetrical, as is the case between most adjacent

generational members, have both parties appealing to the same imperative,

namely of nurturance, reciprocity, and to assert equality of responsibility. The

ecological constraints, such as unreliability of rainfall, are fundamental for

such social and economic organisation. The dominant cultural logic – which

favours permeable boundaries, a decidedly regional world view, and strong

stress on interdependence rather than competition – is thus underlain by an

ecological imperative. Whilst individual autonomy is stressed, egotism by

individuals is not tolerated. Selfishness and egotism are considered

Gurndabarni, or shameless, and the group

will outcast individuals that abuse the ethos of mutual aid. Much time is spent

together, in family groups and as parts of multifamily bands whose members camp

in close proximity to one another. In these domestic situations, there is not

gender dominance of the males over the females due to the norms of kinship that

significantly constrain behaviour after being enculured from a young age.

The distain for arrogance is

also observed with the !Kung. !Kung groups are typified by strong and continual

socialisation and enculturation processes against hoarding and against displays

of arrogance and authority. The proper behaviour of a !Kung hunter who has made

a big kill is to speak of it in passing and in a deprecating manner; if an

individual does not minimise or speak lightly of his own accomplishments, his

friends and relatives will not hesitate to do it for him. As

Richard B.

Lee, Emeritus Professor of Anthropology of University of Toronto, stated in

The

!Kung San: Men, Women and Work in a Foraging Society (1979):

None is arrogant, overbearing, boastful, or

aloof. In !Kung terms these traits

absolutely disqualify a person as a leader and may engender

even stronger forms of ostracism.

Another trait emphatically not found among traditional camp leaders is a desire

for wealth or acquisitiveness. Whatever their personal influence over groups

decisions, they never translate this into more wealth or more leisure time than

group members have. Their accumulation of material goods is never more, and is

often much less, than the average accumulation of the other households in the

camp.

Comparatively, every single

agricultural society throughout history until modernity, from Ancient China to

Tsarist Russia, have been totalitarian, fascist or authoritarian and based on

profound social stratification and hierarchies of power. Private property,

competitive trade, asymmetrical access to resources, and formalised rules led

to the formation of classes. The philosophies of nationalism in ancient

civilisations (or namely its abuse by leaders and the upper classes) and

individualism in modern nation states completely disregarded the common good

and egalitarianism became impossible. The development of agricultural societies

placed new barriers between individuals and flexible access to resources,

because trade often siphoned resources away, because some segments of the

society increasingly had only indirect access to food, because investments in

new technology to improve production focused power in the hands of elites so

that their benefits were not widely shared, and perhaps because of the outright

exploitation and deprivation of some segments of society. The clear class

stratification of health in early and modern civilizations, and the general

failure of either early or modern civilizations to promote clear improvements

in health, nutrition, or economic homeostasis for large segments of their

populations until the very recent past all reinforce competitive and

exploitative models of the origins and function of civilized states.

Labour and Leisure: Hunter Gatherers as the Original Affluent Society

There has been an immensity of

ethnographic research showing that the average weekly working time for a hunter

gatherer is far less than their horticultural, pastoral, agricultural and early

industrial counterparts. Indeed this may seem counterintuitive for a hunter and

gatherer to have an easily life in terms of labour and leisure, but there is

substantial energy expenditure involved in non-hunter gatherer economies. The

seasonal nature of harvesting, the susceptibility to pests and plagues, the

grounds for epidemics, and the incentive for conflict over land all contribute

to offsetting the benefits of surplus and the division of labour that

agriculture yields. Whilst hunter gatherers are subject to episodic patterns of

starvation due to natural disasters and limited ability to store food,

these costs

are offset by their nomadic mobility to search for new food sources and

natural resources. The BBC documentarian Bruce Parry found out this leisurely

existence

when he

lived with Babongo people of Gabon. Indeed, the Hadza are ingenious

survival experts when it comes to their harsh environmental conditions and yet

they still manage to live an affluent life when all their material wants easily

met. A BBC documentary by Ray Mears

shows the rather straightforward

life they Hadza people have. The !Kung people are another profound example

of the effectiveness and ease of hunting and gathering. As Yehudi Cohen, Emeritus

Professor of Anthropology at Rutgers University, points out in

Man in Adaptation: The Cultural Present and

the Biosocial Background (1974):

In all, the adults of the camp worked about

two and a half days a week. Since the average working day was about six hours

long, the fact emerges that !Kung Bushmen, despite their harsh environment, merely

devote from twelve to nineteen hours a week to getting food. Even the hardest

working individual in the camp, a man named Oma, spent a maximum of 32 hours a

week in the food quest.

Conversely, the agricultural

process is a long and labour intensive one: the land must be cleared and the

crops must be planted, irrigated, tended to, protected from pests, harvested

and transported, processed and stored and then prepared for consumption.

Animals as cattle must be domesticated and reared, grazing grounds must be

cleared, cattle must be tended to and protected, herds must be culled, sheep to

be sheared, cows to be milked or butchered, and waste must be disposed of. The

amount of work per capita increases and the amount of leisure decreases with

the development of agriculture where inversely a subsistence labour intensity

is characteristically intermittent, a day on and a day off. Thus agriculture is immensely labour

intensive and agricultural land has diminishing marginal returns due to soil

depletion, water erosion and other environmental weathering processes. As Mark

Nathan, Distinguished Professor of Anthropology at the State University of New

York, notes in Health and the Rise of

Civilization (1999 Yale University Press):

The strategies that sedentary and civilized

populations use to reduce or eliminate food crises generate costs and risks as

well as benefits. These advantages may be outweighed by the greater

vulnerability that crops often display toward climatic fluctuations or other

natural hazards, a vulnerability that is then exacerbated by the specialised

nature or narrow focus of many agricultural systems. The advantages are also

offset by the loss of mobility that results from agriculture, the limits and

failures of various storage systems and the vulnerability of sedentary

communities to epidemic disease, raiding and sacking, and political

expropriation of stored resources.

Peace and Conflict: Mengalah

and Naklik or Bellum Omnium Contra Omnes

There are many perceptions of

violent intertribal warfare and brutish conflicts plaguing hunter gatherer

societies. Indeed, some hunter gatherer societies have been and are ones of

warriors (such as the Surma people of Ethiopia and their stick fighting, and

various Native American tribes), but the misperceptions stem from the

misunderstanding of what hunter gatherers are, what constitutes conflict and

violence, but also an inability to reflect on the history of violence in

agricultural societies. Douglas P. Fry, a Professor of Anthropology at Abo

Akademi University in Finland and the University of Arizona in America, has

done extensive research in cultural variations of conflict resolution and the

nature of peace and violence in societies around the world. His

The

Human Potential for Peace: An

Anthropological Challenge to Assumptions about War and Violence (2006

Oxford University Press) challenges the flawed perceptions of the innateness

and inevitability of violence and warfare in our species and provides an

overview of the existence of peaceful societies throughout history. Fry argues

that the inevitability of conflict is real for all societies but that this does

not at all translate into violence and warfare, and that hunter gatherers have

some of the best examples of conflict resolution systems and norms of peace.

The Semai people, of the Orang

Asli hunter gatherers in the centre of the Malay Peninsula, are a profound

example of this. Their way of life is marked by the archetypal gift economy and

the dichotomy between public and private is non-existent. The Semai proverb “there are more reasons to fear a dispute

than a tiger” is the basis for their social interactions and all conflicts

and disputes are resolved through Becharaa,

a public assembly whereby justice is distributed through communal consensus.

The philosophy of Mengalah, or to

yield, is the norm with the Semai and, through the process of enculturation,

children are taught these principles of peace, cooperation and the preservation

of harmony. Overall, Mengalah manages

to manifest in Semai society as the complete absence of noncompetitive

children’ games, the essential absence of murder and rape, and the

characterisation of social interactions through mutual benefit.

Another hunter gatherer

society where violence is rare is with the Inuit.

Jean L. Briggs,

Emerita Professor of Anthropology at Memorial University of Newfoundland, has

conducted an immensity of ethnographic surveys on the Inuit of the central

Canadian Arctic. In

The Dynamics of Peace

in Canadian Inuit Groups in

The Anthropology

of Peace and Nonviolence, Briggs examines the emotional, educational and

developmental processes of Inuit children in a society of contradictory

beliefs. Whilst a hunting and fishing people, values of nonviolence are equally

essentially in maintaining Inuit society. Briggs observed an essential lack of

interpersonal aggression, from pushing and shoving to even shouting. Children

are taught to internalise cooperative values, abhor interpersonal conflict, to

associate danger (environmental risks) with aggression (animal or personal

hostility), and to realise the possibility of revenge. Moreover, potentially

hostile requests are pacified through non-threatening jokes, the proposals of

commitments are frowned upon, conflicts are expressed through subtle hints and

people counterbalance escalated disputes with emphasised nurturance. The philosophy

of

Naklik underscores Inuit social

interactions entailing the warm concern for the welfare of others.

It can be seen that the

majority of peaceful societies through history and around the world of been

hunter gatherers. The

Encyclopaedia of

Peaceful Societies collated by a team of anthropologists from the United

States provides a systematic overview of the existence and nature of peaceful

societies through history and around the world. Identified are twenty five

peaceful societies where war and violence are essentially absent and twenty of

these societies are indeed hunter gatherer societies. This comes down to the

socioeconomic organisation of these societies as well as the cultural norms

that are taught to children and enforced through various measures.

Comparatively, agriculture fundamentally incentives and leads to warfare. With

the first cities thanks to agriculture came the first standing professional

militaries to protect land and trade routes and to expand land due to

population growth, along with an immensity of other social and economic issues.

The Agricultural Path to Warfare

Every agricultural society

from the ancient civilisations to the modern nation states have been to war on

large scales – from the Peloponnesian War to the Saxon Wars, from the Crusade

to the Mongol conquests, from the Thirty Years War to the American Independence

War, from the Napoleonic Wars to the Crimean War, and from the First World War

to the immensity of civil and ethnic conflicts in Africa and Asia. Overall, far

from being the Hobbesian Bellum Omnium

Contra Omnes, many hunter gatherer societies are far more likely to be

peaceful and some display profound norms of this, such as Semai Mengalah and Inuit Naklik.

Conclusion

Thus, the state of nature is

not as brutish or as poor as Hobbes proposed in 1651. Indeed, whilst living as

a nomadic foraging might not be everyone’s cup of tea, it does indeed seem that

is one of less work, less violence and more social and economic equality – not that

these traits are normatively good or bad. Empirically, the average person in a

hunter gatherer society would have more access to food, have to work less and

have more leisure time and be subject to less violence than the average person

in an agricultural society throughout history. Hunting and gathering has all

the strengths of its weaknesses. Periodic movement and restraint in wealth and

adaptations, the kinds of necessities of the economic practice and creative

adaptations the kinds of necessities of which virtues are made. Precisely in

such a framework, affluence becomes possible. Mobility and moderation put hunters

and gatherers ends within range of their technical means. An undeveloped mode

of production is thus rendered highly effective. The hunter gatherers life is

not as difficult as it looks from the outside. Indeed the higher level of

inequality agriculture permits allows some people to be completely better-off

than any hunter-gatherer, but average living standards plummet even as pure

quantity of people alive goes way up, as per Derek Parfit’s

repugnant

conclusion along the lines of the Malthusian growth model.

Even if the Hobbesian Leviathan

was accurate in being the life in the state of nature is brutish and poor, what

does that make the life in the state of agricultural based societies? The

archaeological and palaeopathological evidence shows that life expectancy in

the Neolithic, Bronze Age, Iron Age, Middle Ages, and Early Modern period right

up until the Renaissance and scientific revolution was far less than that of

hunter gatherers. Indeed, the Swedish life expectancy

in 1750 was on par with hunter gatherers around the world.

The Swedish Life Expectancy of the 1750s and

Hunter Gatherer Life Expectancy

Life in agricultural societies,

from the Neolithic to early modern history (and still for developing nations) was

a plagued, unfair, chronic, violent, and politically exploited existence. It

has only been with the scientific revolution and the spread of liberalism and

civil rights have agricultural based societies been able to match the health

and socioeconomic benefits of hunter gatherers.

The only reason agriculture

has become dominant through history is because of the massive capacity for reproduction

of the human species it allows. Natural selection does not care about the

social, economic or indeed medical realities an organism exists in – all it

cares about is replicating and thanks to agricultural surplus this can take

place. Population density dramatically and exponentially grew with the

invention of agriculture during the Neolithic transition, and yet was marked by

lower life expectancy than those living in the Palaeolithic hunter gatherer

subsistence. Agriculture does indeed have benefits, but these

benefits are largely short term. Even if you reject the normative position taken by Jared Diamond

in describing agriculture as the worst invention in human history, his analysis in

Guns, Germs and Steel as to how agricultural societies dominant others is still completely valid. But

just because agricultural societies have been the dominant and yielding the

largest populations, it does not necessarily make them the best empirically to

live in. Natural selection does not care about subjective wellbeing or the

socioeconomic conditions an organism lives in and agricultural societies,

whilst producing massive inequalities and health hazards, enabled the human

species to exponentially grow. Indeed hunter gatherers would have all taken the

step to agriculture if their environmental conditions allowed.

--

Tasman Bain is a second year

Bachelor of Arts (Anthropology) and Bachelor of Social Science (International

Development) Student at the University of Queensland. He is interested

evolutionary anthropology, public economics and philosophy of science and enjoys

endurance running, reading Douglas Adams, and playing the glockenspiel.

.jpg)