“Where there is a visible

enemy to fight in open combat, the answer is not so difficult. Many serve, all

applaud, and the tide of patriotism runs high. But when there is a long, slow

struggle, with no immediately visible foe, your choice will seem hard indeed.” –

President John F. Kennedy to the graduating class of the United States Military

Academy at West Point in 1962.

"The Last Stand of the 44th Regiment at Gandamak" painted by William Barnes Wollen in 1898 depicts the last stand near Gandamak village on the 13 January 1842 by the survivors of the British retreat from Kabul.

In 1839, British forces

invaded Afghanistan and captured Kabul. By 1842 the occupation sparked uprisings

by the Afghani population which soon routed British forces. The commanding

officer of the British Garrison in Kabul, Major General William Elphinstone,

planned a retreat of the garrison which consisted of British and British Indian

soldiers and their wives and children. The retreating column was continuously

harassed by Afghani tribesmen and they were all eventually either massacred in the

valley pass of Gandamak, died from the harsh wintery conditions and lack of

supplies, or were captured. Only one member of the garrison, an assistant

medical officer by the name of William Brydon, both survived the ordeal and

made it back to the British garrison of Jalalabad.

Ever since this massacre near

the village of Gandamak in January 1842, Afghanistan has proved the setting for

risky geopolitical jousts, dangerous strategic manoeuvring, and folly military

interventions by global great powers. Whilst the motives for the invasions of Afghanistan were different for each superpower, the course and outcomes of their conflicts have all arguably been analogous – indeed such is the legacy of Gandamak. The British invaded for strategic and imperial rationales – seeking to counter Russian influences in Central Asia and to protect Imperial India. The Soviets invaded for strategic and political rationales – seeking to counter American influences on the southern flanks of the USSR and to support the Afghani communist regime of the Saur Revolution. The Americans invaded for security and political rationales – seeking to rid the world of the Taliban that were supporting Al Qaeda, to kill or capture Osama bin Laden, and to bring capitalism and democracy to the country. Indeed the imperial and military misadventures by the great powers profoundly reflect an ignorance and misunderstanding of the diversity of Afghani political and cultural dynamics. Suffice to say, as Seth Jones has termed,

Afghanistan has been the Graveyard

of Empires through changing international and regional strategic, military,

demographic and socioeconomic factors - the

Great Game of the 19th century, the Cold War of the 20th

century, the concurrent War on Terror or Global

Counterinsurgency as per David Kilcullen, and the

emerging New Great Game.

Afghan children beneath graffiti of a crossed out pistol with writing that reads "freedom" in Kabul (20 June 2012 | Associated Press / Ahmad Nazar).

Now in 2012, 170 years since the

withdrawal of British forces and their massacre in the First Anglo-Afghan War and

23 years since the withdrawal Russian forces and their loss of the Soviet

invasion, the troops of the 2009 surges by the United States have been

demobilised. Indeed the

history of Gandamak has been stirring up similarities between the Afghani

ventures by British forces and ISAF forces. The United States Secretary of

Defence, Leon Panetta, announced

the finalisation of the withdrawal whilst in New Zealand in September

without pomp or circumstance in the American or international media. At the NATO

Summit in Chicago in May this year, an exit

strategy and transition were planned entailing decreases of the NATO led

ISAF troop commitments with incremental handovers to Afghani security forces. Other

member nations of ISAF, such as Australia, have also begun to scale down

operations and troop commitments. There is seemingly recognition by the public

and governments of ISAF member nations that a continued prolonged and sustained

military presence in Afghanistan has become too detrimental due to overriding political,

financial and human costs.

Indeed, the international

military presence in Afghanistan, which has been a continuous conflict since

2001, has largely turned into a quagmire. Efforts to train Afghani forces have

resulted in growing

numbers of “green on blue” attacks. Levels

of corruption and obstruction in the Afghani authorities have been ride. The

increasing

utilisation of drone strikes, surgical or not, as well as extrajudicial

killings as tools of statecraft to fight insurgents in the contested Federally

Administered Tribal Areas and in the Afghani-Pakistani border more broadly have

killed civilians, categorically exacerbating existing conflicts and facilitated

radicalisation. Continued

deaths and wounding of troops by Improvised

Explosive Devices have been unforgiving. The noted troop surges, whilst may

have appeared an effective strategic decision hoping to mimic the success seen

by the Iraq troop surges, have operationally manifested as poor tactical deployments that have been proven ineffective at stemming the flow of violence and Taliban movement.

Recent phenomena, such as the Arab Spring, along with long term economic trends, namely the Asian Century, have profound geopolitical and strategic implications for the conflict in Afghanistan. The pivot that Central Asia has historically offered is drastically changing due to economic, technological and social change in the wider Middle East and Asia Pacific regions. The British made this mistake through pouring troops in from India in the nineteenth century as did the Soviets from their border in the 20th century. Now the Americans and ISAF are scaling down troops whilst attempting to train Afghani security forces and bequeath a new self-dependence. The Soviet campaigns of carport bombing of villages with attack helicopters and plane strikes are analogous to current drone strikes by the United States. Indeed a tragedy presents itself – Mikhail Gorbachev couldn't win the war in Afghanistan and yet couldn't acknowledge this fact. Although Gorbachev, a moderate in the politburo, planned a withdrawal deadline of Soviet forces, military expenditure actually increased until Soviet forces crossed the last bridge out of Afghanistan. Similarly, Barack Obama faces an increasingly unwinnable conflict and yet steadily increased American forces until scaling back the troop surges just last month. Indeed, Afghanistan is a war without an end. Fundamentally, Afghanistan proves unstable and, as David Petraeus notes, any progress that has been actualised is fragile and reversible.

Recent phenomena, such as the Arab Spring, along with long term economic trends, namely the Asian Century, have profound geopolitical and strategic implications for the conflict in Afghanistan. The pivot that Central Asia has historically offered is drastically changing due to economic, technological and social change in the wider Middle East and Asia Pacific regions. The British made this mistake through pouring troops in from India in the nineteenth century as did the Soviets from their border in the 20th century. Now the Americans and ISAF are scaling down troops whilst attempting to train Afghani security forces and bequeath a new self-dependence. The Soviet campaigns of carport bombing of villages with attack helicopters and plane strikes are analogous to current drone strikes by the United States. Indeed a tragedy presents itself – Mikhail Gorbachev couldn't win the war in Afghanistan and yet couldn't acknowledge this fact. Although Gorbachev, a moderate in the politburo, planned a withdrawal deadline of Soviet forces, military expenditure actually increased until Soviet forces crossed the last bridge out of Afghanistan. Similarly, Barack Obama faces an increasingly unwinnable conflict and yet steadily increased American forces until scaling back the troop surges just last month. Indeed, Afghanistan is a war without an end. Fundamentally, Afghanistan proves unstable and, as David Petraeus notes, any progress that has been actualised is fragile and reversible.

Theorised, developed and put

forth by maverick military commanders and strategists thinking outside of the

box at the Pentagon, counterinsurgency strategy was hailed as a panacea and

game changing for the future of warfare. The pioneers

of counterinsurgency, figures such as David Petraeus, John Nagl, David

Kilcullen, and Herbert McMaster, have marked the rise of a new intellectual

warrior class: combat soldiers with doctorates and higher academic

qualifications. Counterinsurgency at its crux is an operational strategy

centred on protecting population centres from insurgents, civil institutional

capacity building, and information operations. Indeed the work by former

Australian Army officer, government advisor and political anthropologist Dr

David Kilcullen on counterinsurgency strategy has been fundamentally important.

His theory of the “accidental guerilla is a key to understanding the

insurgencies around the world throughout modern history. A complex range of

diagrams and flow charts explained in verbose management language with a focus

on quantitative methods are all now part and parcel of the strategy of

counterinsurgency as it manifests in the academic literature and military

strategy. The pioneers of counterinsurgency led the charge for

counterinsurgency strategy to be adopted by the United States Military as

official doctrine by presenting it as the grand unified theory of everything

for the unconventional warfare. Consequently the United States Military

formulated the Counterinsurgency

Field Manual and the Army

and Marine Corps have implemented training programs, established research

centres, and formulated operational tactics guidelines for small frontline

units. The United States Department of State formulated a counterinsurgency

guide for the civil agencies of the United States Government. The NATO led

ISAF commanders have also established

counterinsurgency manuals. Indeed, counterinsurgency strategy has become

the orthodoxy for unconventional warfare for the United States Military.

Fundamentally though, counterinsurgency

has largely failed at countering the widespread insurgency in Afghanistan and yet

it is becoming almost dogmatic and a “one size fits all” strategy for

commanders, planners and policymakers. Critically, counterinsurgency is largely

becoming the unquestioned orthodoxy and an institutionalised narrative of unconventional

warfare for the United States Military. However there is an ongoing debate

surrounding the effectiveness of counterinsurgency inside the United States

military and government and outside in academia and think-tanks. Even President

John F. Kennedy warned

the graduating class of the United States Military Academy at West Point in

1962 that counterinsurgency is problematic: “Where there is a visible enemy

to fight in open combat, the answer is not so difficult. Many serve, all

applaud, and the tide of patriotism runs high. But when there is a long, slow

struggle, with no immediately visible foe, your choice will seem hard indeed.”

Indeed, unsatisfying

wars are the stock in trade of counterinsurgency; rarely, if ever, will

counterinsurgency end with a surrender ceremony or look akin to the victories

of conventional warfare of history. And yet, unconventional operations, from

counterinsurgency to foreign military assistance, have been the operations

almost exclusively waged by the United States Military since the Vietnam War

though with the notable exception of the First Gulf War. Comparative to other

operational doctrinal changes in the United States Military, counterinsurgency

largely went unquestioned during its emergence and adoption. The doctrine of

AirLand Battle was the official doctrine for the United States Military from

1982 to 1998 and over 110 articles were written for military journals

fundamentally questioning it from 1976 to 1982. Up until its adoption in 2006, there was marginal questioning of counterinsurgency with only significant critiques occurring during its operational and doctrinal implementation. The paradigms of

counterinsurgency that originated with the Boer War, were developed during

conflicts in Malaya, Algeria, Vietnam and Northern Ireland, and then

redeveloped for the insurgency in Iraq have largely failed in Afghanistan.

Moreover, it is still questionable to assume that counterinsurgency and the

associated operations were a success in Iraq. For Afghanistan,

counterinsurgency has been inadequately implemented due to practical failings, ignorantly

theorised through dogmatic assumptions, and fundamentally been an ineffective

foil against the blades of cross cutting ethnic, religious, political

conflicts.

There have been scathing

criticisms against counterinsurgency since the official adoption of it as a

doctrine of the United States Military. There is seemingly

a schism in command structure over the validity

of counterinsurgency with a number of active United States Army Officers openly critiquing their superior officers. United

States Army Colonel Dr Gian Gentile and retired United States Army Colonel

Dr Douglas Macgregor are emblematic of this increasingly

present schism within the United States Military. Outside of the military

there have been systematic articles criticising counterinsurgency. Adam Curtis,

a documentarian with the BBC, wrote

a very insightful examination of counterinsurgency theory critiquing the

American redevelopment of it for Iraq and Afghanistan. Sean Liedman, a United

States Navy Officer and Fellow of the Weatherhead Centre for International

Affairs at Harvard University, writes a dissertation entitled “Don’t Break

The Bank With COIN: Resetting U.S. Defence Strategy After Iraq and Afghanistan”

which offers an insightful critique of counterinsurgency. The website Reassessing

Counterinsurgency also provides a comprehensive library of articles

evaluating counterinsurgency operations and strategy. Critically,

counterinsurgency strategy as has been practiced in Afghanistan is flawed - the troops surges have failed, the ethics of counterinsurgency operations are questionable, and counterinsurgency has become more or less a paradigm of armed nation building.

A bullet-riddled map of Afghanistan painted on a wall of an abandoned school in Zharay district of Kandahar province in southern Afghanistan (9 June 2012 | Reuters / Shamil Zhumatov).

Within the context of the recent demobilisation of the troops from the 2009 surge in Afghanistan order by Obama, it is important to examine the impact of surges associated with counterinsurgency operations and strategy. The primarily rationale for the Afghanistan troop surge in 2009 stemmed from the seemingly successful troop surge in Iraq in 2007 where violence significantly declined. Military commanders and counterinsurgency strategists complained that it was the troop surge that led to the declines in violence however on closer examination that a range of other factors were at play. Certainly there was a decline in violence in Iraq in 2007 coinciding with the troop surge, but this does not equate to causation. The Sunni Awakening, the cease-fire by Mahdi Army, the progressive sectarian segregation of Sunnis and Shiites, and the positive inroads of United States Military, are all critical factors in explaining the decline in violence. Moreover, comparative to Afghanistan, Iraq was more conducive to counterinsurgency operations due to the largely static population centres, working urban infrastructure, relative ethnic homogeneity and better economic conditions. The population of Afghanistan, conversely, is far more rural and sparsely located with more ethnic heterogeneity in Iraq.

Thus the starting rationale for the troop surge in Afghanistan wasn't as clear cut or significant. Failings of the Afghanistan troop surge stem from this misunderstanding of the flaws on the Iraq troop surge, but also from the misunderstanding of the dynamics of the Afghani insurgents or "accidental guerillas" as per Kilcullen. Increasing troop commitments exacerbated

unrest and consequently more accidental guerrillas were killed through the

superior fire power of the United States Military forward operating bases and patrols. Efforts to protect

population centres with increased security failed simply because an increased

troop presence didn't deter the Taliban from making threats and carrying out

punishments with those that explicitly and implicitly cooperated with ISAF. Moreover, cross cutting ethnic and political conflicts were further exacerbated by increased presence of ISAF troops and their efforts in civil cooperation and capacity building. Afghani civilians didn't attend marketplaces patrolled by ISAF troops and migrated away from their troop

bases. Thus the crux of counterinsurgency of population centric operations failed either because increased troops simply deterred civilians before engagement or killed the farmers that infrequently fired at ISAF troops (the "accidental guerillas") thus fostering further radicalisation or alienation. The civil programs of the United States Department of State and the United States Agency for International Development were simply not effective, coordinated or specialised for Afghanistan. There was no sustainable socioeconomic development or long term institutional capacity building by such civil programs which were critically important for support the military operations in the overall counterinsurgency strategy in Afghanistan.

For the surge and its

accompanying counterinsurgency strategy to prevail in Afghanistan, four main

things needed to occur: The Afghan government had to be a willing partner, the

Pakistani government had to crack down on insurgent sanctuaries on its soil,

the Afghan army had to be ready and willing to assume control of areas that had

been cleared of insurgents by American troops, and the Americans had to be

willing to commit troops and money for years on end. Fundamentally, the aforementioned were not attained.

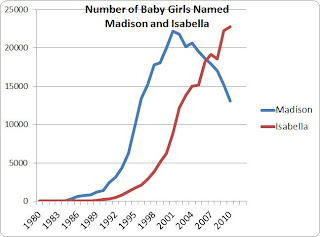

A graph from a ISAF Report in September 2012 measuring Taliban and associated insurgents launched against NATO forces, month by month from January 2008 to August 2012 (obtained via "Military's Own Report Card Gives Afghan Surge an F" from Wired.com).

Coinciding with the rise of

counterinsurgency, there has been a militarisation of the social sciences by

the United States Military. The relationship

between the social sciences, particularly anthropology, and the military

has a contentious history since the Second World War with Iraq and Afghanistan

proving flashpoints. One of the pioneers of counterinsurgency, David Kilcullen,

completed his Doctor of Philosophy in Political Anthropology at the University

of New South Wales with a thesis entitled “The

Political Consequences of Military Operations in Indonesia 1945-99: A Fieldwork

Analysis of the Political Power-Diffusion Effects of Guerrilla Conflict” in

2000 utilising ethnographic methods.

Indeed there has been an acknowledgement of the importance of cultural intelligence in counterinsurgency

and the United States Military have established the, horrifically named, Human Terrain System Project

staffed by social scientists and deployed with combat forces in Iraq and

Afghanistan. Attempts to rectify crosscultural problems and teach intercultural

understanding to the military commanders of ISAF have been made by

anthropologists and other social scientists. Also, there has been extensive

writing on the critical importance of understanding local and regional cultural

dynamics with ethnographic depth for counterinsurgency strategy and

peacekeeping operations. Whilst individuals such as Kilcullen have indeed made

constructive inroads in achieving a cross-culturally competent American

military establishment, a range of external and operational factors have

contributed to renewed failings of counterinsurgency in Afghanistan.

Yet this militarisation of the

social sciences to enhance counterinsurgency efforts in Iraq and Afghanistan

has been met with scepticism and controversy. Ethical objections by the

American Anthropological Association and various social scientists have also

been made. Legal questions pertaining to the combat status of non-military

members of the Human Terrain System Project and their ability to engage with

aspects of war fighting are also important. Organisations such as the Network of

Concerned Anthropologists and Anthropologists for Justice and

Peace have been active

and vocal in criticising counterinsurgency and the Human Terrain System

Project. The Network of Concerned Anthropologists has even published a book

entitled The

Counter-Counterinsurgency Manual that systematically critiques

counterinsurgency strategy and the employment of social scientists by the

Military. David Price, a Professor of Anthropology at St. Martin's College has

also written the comprehensive book entitled Weaponising

Anthropology: Social Science in Service of the Militarized State which also

rebukes the militarisation of the social sciences.

United States Army soldiers of the 173rd Airborne Brigade Combat Team, carry a wounded colleague after he was injured in an IED blast during a patrol in Logar province (13 October 2012 | AFP / Munir Uz Zaman).

The paradigm of nation

building is arguably a valid concept of international development; however within

counterinsurgency operations it is pursued primarily by the military. This is

only inevitably due to the massive difference between funding and resources of

the United States Military and the foreign civil development programs of the

United States Government. Yet such a situation is not ideal. Thus it is accurate

to classify counterinsurgency as armed nation building conducted by an

organisation not versed in civic development.

Such coincides with the

existential crisis the United States Army is going through over what role it is

to take in a post-Cold War and post-911 world. Pentagon officials and strategic

theorists believe the future will be dominated by sea-air warfare,

cyberwarfare, and unconventional warfare. Indeed the historical role of the Army

of infantry operations and conventional warfare is now defunct. Therefore, the top

United States Army officers believe that they must adapt to the changing

strategic and security environment or risk decreased funding and irrelevancy. Though

whilst adapting to unconventional warfare may seem a critical and imperative

decision for the United States Army and military at large, it is merely a

superficial approach and ignores the underlying factors for such conflict in

the first instance. Moreover, the adaptation to counterinsurgency and

asymmetrical warfare by the United States Military arguably incentivises and

fosters an interventionist posture. A change of posturing of the United States

Military from conventional forces towards a holistic counterinsurgency doctrine

will likely incentivise continued entrances into unconventional conflicts that

would traditionally not have been a consideration. Gian Gentile, a United

States Army Colonel and History Professor at West Point, posits that

overconfidence in the validity of counterinsurgency incentivises future

interventions into conflicts but also prevents the development of capabilities

to counter conventional threats.

A United States Army soldier of the 1st Airborne Brigade Combat Team of the 82nd Airborne Division fires a machine gun at insurgent forces in Ghazni province (15 June 2012 | U.S. Army / Mike MacLeod).

Rather than have the United States Military adapt to asymmetrical warfare, efforts must be taken to

increase the funding and resources of civil and humanitarian programs such as

USAID and various organisations of the Department of State. Only then can the

underlying conditions that foster radicalisation, extremism and the accidental guerilla syndrome be dealt with. Insurgencies will continue to exist despite

the exertions of counterinsurgency operations by the United States Army and

Marine Corps. Thus rather than increasing military presence, non-military

humanitarian and development capabilities need to be favoured. Rather than

having the capabilities of drone strikes and counterinsurgency operations, the

United States and ISAF as a whole should be focusing on civil, stabilisation

and capacity building programs. Indeed, whilst military forces will be required

to provide security and protection to such civil programs, the military option

should not be the first option of choice or even the tenth. Rather than drone

strikes and troop surges, ISAF must focus on civil capacity building through

education and social, economic and infrastructural development projects, and

through stabilisation policing and security assistance. Indeed ISAF should be

focusing on security assistance and socioeconomic development, rather than

combat operations with drones and troops. All other avenues are akin to

attempting to crack a nut with a jackhammer.

--

Tasman Bain is a second year Bachelor of Arts (Anthropology) and Bachelor of Social Science (International Development) Student at the University of Queensland and is currently undertaking a Summer Research Scholarship at the Sustainable Minerals Institute at the University of Queensland. He is interested economic, evolutionary and medical anthropology and enjoys endurance running, reading Douglas Adams, and playing piano.

.jpg)